TL;DR: Considering the science and mysticism of Arthur C. Clarke.[1] |

In his 1953 novel Childhood’s End, Arthur C. Clarke does what he does best: examines the evolution of humanity through two lenses: one of science and one of mysticism. I’m late coming to this work, but I’m reminded of his main theme in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); i.e., the consequences of humanity’s ever-increasing technological sophistication on its place in the universe. Both novels deal with the next phase of humanity’s evolution, precipitated by alien forces that aren’t quite comprehensible; however, while I have always seen the latter work as an optimistic view of this inevitability, Childhood’s End is sombre and lugubrious at best.

When Clarke wrote the novel, World War 2 had literally just ended with a bang. The hydrogen bomb was at once the symbol of humanity’s greatest technological ingenuity while also a harbinger of its potential for self-annihilation. Clarke’s novel positions humanity at this crucial time in its history, while its fate could still go either way. Childhood’s End predicts the space race, something that wouldn’t come to the international stage until a decade later, but its main driving force begins when humanity’s choice in its own fate is removed by the coming of the Overlords.

Now, I have to say, I find Childhood’s End reads a bit like a technical manual. The prose is often mechanical; the characters are stiff at best and robotic at worst. I don’t understand the “jokes” that he points out to me, and the narratorial voice is like a effete academic after a bit too much claret. The novel is expansive in scope — the action takes place over about a century-and-a-half — and the setting is primarily on Earth, though there is some space travel and astro-projection. The scenes of dialog were often difficult to read — the characters seemed to be little more than stereotypes in the middle of the novel, bracketed by scientists and the Overlords. To me, the most interesting parts of the novel were the future histories: the third-person narrator became the voice of exposition, telling the facts of human development after the coming of the Overlords. In many ways, Childhood’s End is a test case for humanity: what happens when human conflict comes to an end? Indeed, as a colleague and I were discussing the other day, would we even remain human if we ended violence and war? Is conflict an integral aspect of humanity?

It sounds as if I’m being too hard on Clarke’s writing. Maybe. However, I might also suggest that Clarke meant to write his characters this way. After all, the most tedious parts of the novel were the dramatic scenes in the middle, called “The Golden Age.” Middles are often tedious. The “Earth and the Overloads” shows the coming of the aliens and humanity’s initial reactions, and “The Last Generation” plays out the drama. Perhaps Clarke is illustrating his difficulty with utopia in “The Golden Age.” With no contention, life begins to become stagnant, lacking adventure and challenge: “When the Overlords had abolished war and hunger and disease, they had also abolished adventure.”[2] Add to that Overlord Karellen’s injunction about man’s place in the universe: it is only on the Earth and does not include space travel. He states:

Your race, in its present stage of evolution, cannot face that stupendous task. One of my duties has been to protect you from the powers and forces that lie among the stars — forces beyond anything you can imagine. [. . .] It is a bitter thought, but you must face it. The planets you may one day possess. But the stars are not for Man.[3]

The key word in his speech is “evolution.” Clarke’s novel seems to posit that humanity’s ability to cope with the environment is determined by that environment. That is, in its current form, humanity is not capable of moving too far beyond Earth, or its natural environment. In order to leave the Earth in any appreciable way, humans must evolve. This means, it seems, losing our humanity.

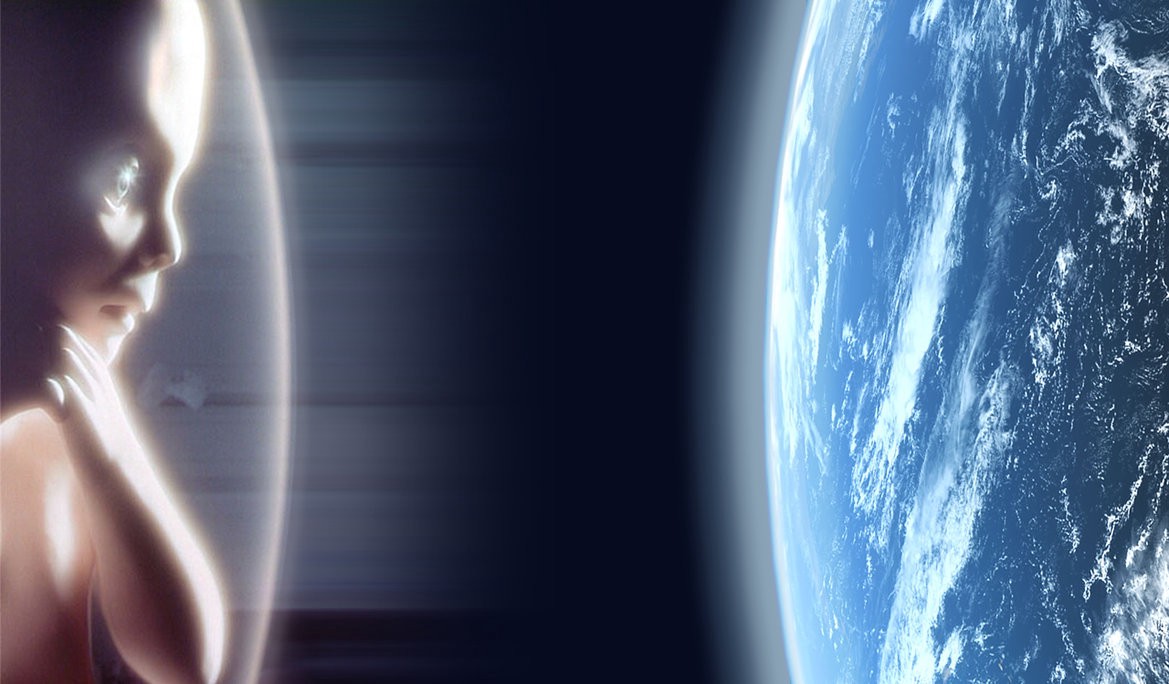

Now, 2001 is not like that. It is an odyssey, and in an odyssey, the final stop is always home. True to form, the last scene in both the film and novel, the Star-Child returns to Earth, ushering in the next evolutionary step of humanity. One could argue the definition of “home” has changed, too, like in Homer’s original Odyssey. “Home” for the Star-Child is now larger than a single planet or solar system; it must lead the way for humanity. However, the last chapter of Childhood’s End has the newly evolved post-humans leaving Earth for the stars. Not only do they leave, but Earth disintegrates, as if by the exodus of the children she produced, the Earth no longer has a purpose in the cosmos. By the end of the novel, humanity, in its current form, is extinct.

Therefore, Clarke’s exposition of humanity’s utopia in “The Golden Age” is necessarily a reflection of what humanity has been evolving toward. It is necessarily imperfect because the nature that created humanity is local, finite, and imperfect itself. Whatever humanity creates might help its position on the Earth, but ultimately, perhaps, humans cannot make the next transition alone.

One of the cheesiest scenes in Childhood’s End is the post-party Ouija board seance. I remember hearing this scene (I listened to the novel for the first time last summer) while driving though Kentucky or Tennessee. I was unimpressed, but the whole rest of the novel centers around the mystical revelations of this pivotal moment: Jan’s non-scientific confirmation of the Overlords’ star, and Jean’s “paraphysical” connection with the Overmind. The novel — scientific, sociological, political, and factual up until this point — becomes more mystical, “supernormal,” and occultist.

Looking at it allegorically, the Overlords seem to represent the products of pure science. They are the masters of all that is tangible — space travel, politics, psychology, etc. There is the Overmind, something that exists beyond the physical realities of this universe, yet has certain mystical connections with it. Then there are humans: they seem to be products of the measurable, quantifiable world, but heading along an evolutionary path that aligns some of them with the Overmind, not the Overlords.

In fact, one of the more poignant parts of the novel lies near the end, when Karellan explains to Jan, now the last human, that the name “Overlords” is tinged with irony: they, too, are products of a certain evolutionary path that will never know the Overmind:

| “ | At the end of one path were the Overlords. They had preserved their individuality, their independent egos: they possessed self-awareness and the pronoun “I” had a meaning in their language. They had emotions, some at least of which were shared by humanity. But they were trapped, Jan realized now, in a cul-de-sac from which they could never escape. Their minds were ten — perhaps a hundred — times as powerful as men’s. It made no difference in that final reckoning. They were equally helpless, equally overwhelmed by the unimaginable complexity of a galaxy of a hundred thousand million suns, and a cosmos of a hundred thousand million galaxies.[4] | ” |

The ending is bittersweet. The Overlords cannot help feeling sorry for the current humans that they helped to civilize and evolve, but at the same time they envy humanity’s ability to grow beyond the measurable galaxy. They exist in their current form, and they have the knowledge that they have reached the pinnacle of their evolution. Perhaps this is Clarke’s equivalent of lacking wonder beyond the real.

I think that ultimately Childhood’s End is a successful novel. Yet, its end is one of pathos, more of a sense that something is lost. Perhaps more accurately, it’s a sense that we humans, in our current evolutionary form, are so limited. We will be lucky to survive self-annihilation, to grow beyond greed and materialism, to achieve equality, and to live in peace. I’m left with the feeling that even if we do succeed in these Earthly endeavors, there is something we, in our “present state of evolution,” will never achieve.

notes

- ↑ Originally published on October 25, 2010.

- ↑ Clarke, Arthur C. (1990) [1953]. Childhood's End. New York: Del Rey. p. 85.

- ↑ Clarke 1990, p. 129.

- ↑ Clarke 1990, p. 199.