More actions

Created page. |

m Added cat. |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{Jt|title=''Blade Runner'' as Cyberpunk}}<br /> | ||

{{Big|Ridley Scott’s 1982 classic may not be “[[Cyberpunk|cyberpunk]],” but it definitely has elements of the genre.}} | {{Big|Ridley Scott’s 1982 classic may not be “[[Cyberpunk|cyberpunk]],” but it definitely has elements of the genre.}} | ||

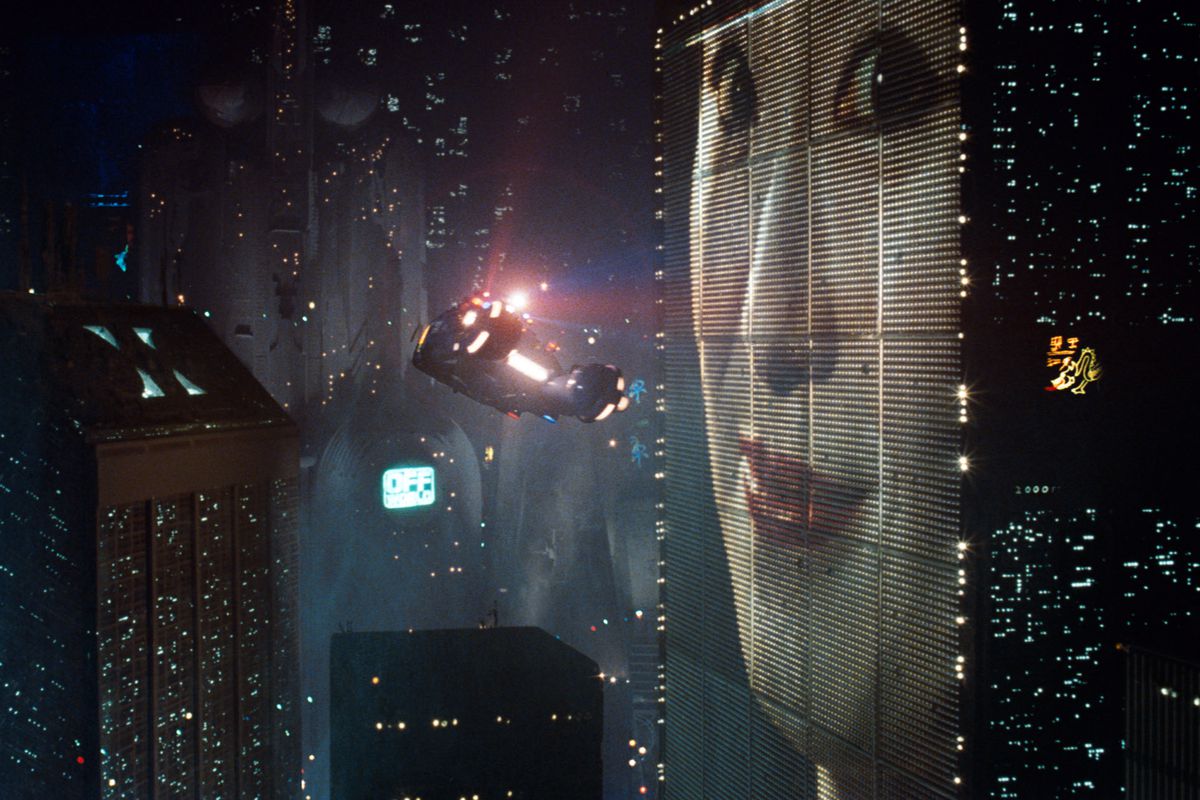

{{dc|I}}{{start|’ve always thought ''Blade Runner'' had the look-and-feel}} of [[cyberpunk]]. This aesthetic might be its greatest contribution to the genre, thus making it the film’s best cyberpunk characteristic. The world of ''Blade Runner'' is post-apocalyptic—if not literally after World War Terminus like in {{c|Philip K. Dick|Dick}}’s novel ''Androids''—then certainly human progress has become like a virus for planet Earth. Humanity is dense and dirty on the streets, and represents a mélange of cultures all boiling together in a stew of languages, cultures, styles, tech, and vices. It’s now a wasteland dominated by industry, vague cityscapes supported by crumbling technologies. At its top sits the Tyrell Corporation: its two buildings dominating the landscape, like twin Mount Olympuses dominating the technoscape. | |||

<div class="res-img">[[File:027 blade runner theredlist.0.jpg]]</div> | <div class="res-img">[[File:027 blade runner theredlist.0.jpg]]</div> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Up until this point, Rachael has been a pretty solid cyberpunk heroine. When Deckard first meets her at the Tyrell Corporation, she is smooth, confident, and styling. She handles herself and Deckard with the ease and grace we might expect from Gibson’s Molly. Also like Molly, Rachael has a crisis that determines her future; however, while Molly was able to gain strength from her experiences as a meat puppet and Johnny’s death, Rachael’s new-found knowledge that’s she’s a replicant cripples her. For some reason, she goes to Deckard—the guy least capable of showing her empathy or compassion—after Tyrell ostensibly kicks her out (just like a god). Deckard handles her much like he does Zhora and Pris: dominating her with his gun—this time the fleshy one in his pants. Rachael loses her identity, becoming more like one of J.F. Sabastian’s toys rather than an autonomous entity. “Too bad she won’t live,” Gaff says to Deckard at the end, perhaps knowing that the Bladerunner killed her already. | Up until this point, Rachael has been a pretty solid cyberpunk heroine. When Deckard first meets her at the Tyrell Corporation, she is smooth, confident, and styling. She handles herself and Deckard with the ease and grace we might expect from Gibson’s Molly. Also like Molly, Rachael has a crisis that determines her future; however, while Molly was able to gain strength from her experiences as a meat puppet and Johnny’s death, Rachael’s new-found knowledge that’s she’s a replicant cripples her. For some reason, she goes to Deckard—the guy least capable of showing her empathy or compassion—after Tyrell ostensibly kicks her out (just like a god). Deckard handles her much like he does Zhora and Pris: dominating her with his gun—this time the fleshy one in his pants. Rachael loses her identity, becoming more like one of J.F. Sabastian’s toys rather than an autonomous entity. “Too bad she won’t live,” Gaff says to Deckard at the end, perhaps knowing that the Bladerunner killed her already. | ||

<div class="res-img">[[File:Deckard.jpeg</div> | <div class="res-img">[[File:Deckard.jpeg]]</div> | ||

Deckard, too, has his headspace toys. He uses the Voight-Kampff (pictured above—note, too, Deckard’s 80s/cyberpunk clothes) to test Rachael’s emotional reactions to a series of questions: measuring her meat for the appropriate empathic responses. Since she is a Nexus 6, the meat has been programmed with memories (represented in the film by photographs) to simulate empathy—remember Tyrell’s “more human than human” for some reason. Indeed, the replicants do seem emotionally more alive than the humans in this film. We are meant to assume that Deckard is human, but hints throughout suggest he might be a replicant. Indeed, the cyberpunk hero does walk the line between headspace and meatspace, usually preferring the former. Perhaps it’s Deckard’s profession as a killer that has made him cold and machine-like, for the predator’s (console cowboy’s) life is one of necessary isolation. When he’s not out killing, he’s alone in his cave with a bottle of bourbon, maybe the film’s version of the Penfield Mood Organ. | Deckard, too, has his headspace toys. He uses the Voight-Kampff (pictured above—note, too, Deckard’s 80s/cyberpunk clothes) to test Rachael’s emotional reactions to a series of questions: measuring her meat for the appropriate empathic responses. Since she is a Nexus 6, the meat has been programmed with memories (represented in the film by photographs) to simulate empathy—remember Tyrell’s “more human than human” for some reason. Indeed, the replicants do seem emotionally more alive than the humans in this film. We are meant to assume that Deckard is human, but hints throughout suggest he might be a replicant. Indeed, the cyberpunk hero does walk the line between headspace and meatspace, usually preferring the former. Perhaps it’s Deckard’s profession as a killer that has made him cold and machine-like, for the predator’s (console cowboy’s) life is one of necessary isolation. When he’s not out killing, he’s alone in his cave with a bottle of bourbon, maybe the film’s version of the Penfield Mood Organ. | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

In his apartment, Deckard uses another cyberpunky headspace toy: his photograph analyzer. Cyberpunk heroes also use the virtual world to hunt for clues, and Deckard is no exception. If photographs represent memory, then the computer probes Leon’s memory to find Zhora buried under the virtual kipple. This scene is memorable because of the technology, and it’s one time that Deckard seems almost human. After all, the meatspace in this world is pretty depressing and this machine is the closest thing to the Internet in the future of 1982. | In his apartment, Deckard uses another cyberpunky headspace toy: his photograph analyzer. Cyberpunk heroes also use the virtual world to hunt for clues, and Deckard is no exception. If photographs represent memory, then the computer probes Leon’s memory to find Zhora buried under the virtual kipple. This scene is memorable because of the technology, and it’s one time that Deckard seems almost human. After all, the meatspace in this world is pretty depressing and this machine is the closest thing to the Internet in the future of 1982. | ||

OK, I’m sure I just scratched the surface here. In what other ways could Blade Runner be called cyberpunk? I’d like to hear your thoughts. | OK, I’m sure I just scratched the surface here. In what other ways could ''Blade Runner'' be called cyberpunk? I’d like to hear your thoughts. | ||

{{2013}} | {{2013}} | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

[[Category:Film]] | [[Category:Film]] | ||

[[Category:Science Fiction]] | [[Category:Science Fiction]] | ||

[[Category:Ridley Scott]] | |||

Latest revision as of 07:35, 30 May 2022

Blade Runner as Cyberpunk

Ridley Scott’s 1982 classic may not be “cyberpunk,” but it definitely has elements of the genre.

I’ve always thought Blade Runner had the look-and-feel of cyberpunk. This aesthetic might be its greatest contribution to the genre, thus making it the film’s best cyberpunk characteristic. The world of Blade Runner is post-apocalyptic—if not literally after World War Terminus like in Dick’s novel Androids—then certainly human progress has become like a virus for planet Earth. Humanity is dense and dirty on the streets, and represents a mélange of cultures all boiling together in a stew of languages, cultures, styles, tech, and vices. It’s now a wasteland dominated by industry, vague cityscapes supported by crumbling technologies. At its top sits the Tyrell Corporation: its two buildings dominating the landscape, like twin Mount Olympuses dominating the technoscape.

Eldon Tyrell is the god of his world: that of “more human than human” replicant production. The replicants are meatspace hacks, cyborgs of flesh and bone to Tyrell’s Dr. Frankenstein. The longevity of his monsters is a built-in four years, enough time to be slaves, but not enough to become human beings. The Tyrell Corporation makes zombies for service in human colonies: techno-slaves for a brave new world practically indistinguishable from the humans they serve; these slaves are supposed to be devoid of emotion and empathy and therefore easily controlled. This has cyberpunk written all over it: the programs trying to rewrite their code in order to postpone death. The replicants are victims of their own dying meat, and they have stolen a ship and come back to meet their maker. (Is the maker ever able to help though?)

Yet, returning to earth is illegal. I wonder why? Is this to keep the monsters out of the Eden in which they were created? Punishment for returning is “retirement”: death at the hands of the Bladerunner. Enter Rick Deckard: our cyberpunk hero with a gun. The male protagonist in cyberpunk literature is often geeky and not physically imposing. The cyberpunk hero’s domain is headspace, usually leaving the physical challenges of meatspace to the female protagonist. Deckard fits this characterization fairly well: he is physically ineffectual, most of the time getting the shit kicked out of him by the replicants, running from them himself, or using his big gun to give him the predatory advantage. Against Leon and Roy, Deckard would have met his end without outside intervention. Physically, he was no match for them. This might be true, too, for the female replicants Zhora and Pris, but he had his gun for those encounters; he shoots Zhora in the back as she flees through the streets, and Pris he shoots in the stomach, letting her flail around on the floor for a moment before the actual kill shot. Deckard does have a way with the ladies.

It’s Rachael that saves Deckard from Leon. After Leon watches Deckard murder retire Zhora, the replicant confronts the Bladerunner, easily disarming him. Leon beats Deckard for a bit before going in for the kill. Rachael shows up with Deckard’s gun, and shoots Leon in the head.

Up until this point, Rachael has been a pretty solid cyberpunk heroine. When Deckard first meets her at the Tyrell Corporation, she is smooth, confident, and styling. She handles herself and Deckard with the ease and grace we might expect from Gibson’s Molly. Also like Molly, Rachael has a crisis that determines her future; however, while Molly was able to gain strength from her experiences as a meat puppet and Johnny’s death, Rachael’s new-found knowledge that’s she’s a replicant cripples her. For some reason, she goes to Deckard—the guy least capable of showing her empathy or compassion—after Tyrell ostensibly kicks her out (just like a god). Deckard handles her much like he does Zhora and Pris: dominating her with his gun—this time the fleshy one in his pants. Rachael loses her identity, becoming more like one of J.F. Sabastian’s toys rather than an autonomous entity. “Too bad she won’t live,” Gaff says to Deckard at the end, perhaps knowing that the Bladerunner killed her already.

Deckard, too, has his headspace toys. He uses the Voight-Kampff (pictured above—note, too, Deckard’s 80s/cyberpunk clothes) to test Rachael’s emotional reactions to a series of questions: measuring her meat for the appropriate empathic responses. Since she is a Nexus 6, the meat has been programmed with memories (represented in the film by photographs) to simulate empathy—remember Tyrell’s “more human than human” for some reason. Indeed, the replicants do seem emotionally more alive than the humans in this film. We are meant to assume that Deckard is human, but hints throughout suggest he might be a replicant. Indeed, the cyberpunk hero does walk the line between headspace and meatspace, usually preferring the former. Perhaps it’s Deckard’s profession as a killer that has made him cold and machine-like, for the predator’s (console cowboy’s) life is one of necessary isolation. When he’s not out killing, he’s alone in his cave with a bottle of bourbon, maybe the film’s version of the Penfield Mood Organ.

In his apartment, Deckard uses another cyberpunky headspace toy: his photograph analyzer. Cyberpunk heroes also use the virtual world to hunt for clues, and Deckard is no exception. If photographs represent memory, then the computer probes Leon’s memory to find Zhora buried under the virtual kipple. This scene is memorable because of the technology, and it’s one time that Deckard seems almost human. After all, the meatspace in this world is pretty depressing and this machine is the closest thing to the Internet in the future of 1982.

OK, I’m sure I just scratched the surface here. In what other ways could Blade Runner be called cyberpunk? I’d like to hear your thoughts.