Garfinkle’s Celestial Matters

I’ve been thinking lately about being human. This is not necessarily a new thing for me, but, especially when I teach new media, I find myself drawn to what we humans do and what it is that defines us as human. I understand that “human” has both a physical and discursive reality; i.e., we have our physical relationship to our environments that we experience through our body and its senses, and an ever-changing and evolving conception of ourselves in relation to the universe. Call the first relationship that of science and the latter that of philosophy. I understand that this distinction is wrought with problems, but it’s the distinction itself that concerns the scientific myth that we humans seem to privilege: that of order.

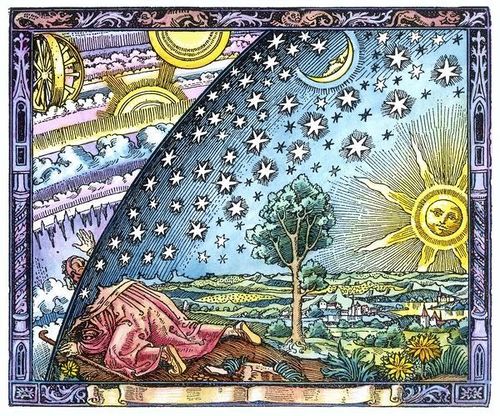

Part of being human is attempting to reconcile our relationship with nature. Nature, itself, is a tricky word—many things have become naturalized; for example, a woman’s biological clock, human curiosity in the unknown, gender, patriarchal privilege. I mean the physical universe that we find ourselves in and that thousands of years of mythology has tried to pattern and order so that our limited, but evolving, human intellect can make our environment more sensical and less chaotic. As our intellect evolved, our stories became more complex and subtle to mirror our increasing understanding of universe. We have progressed far, but there’s still much we have yet to fathom.

Astronomy has been one way that humanity seems to have always embraced as holding the keys to understanding. Whether is has been explained as the perfect abode of the gods, the offspring of Gaea, Uranus, or the abode of planets and galaxies, humans have always looked to the sky as a source of mystery and certainty—a place of grandeur and order in which lies the answers to many of our questions about ourselves and how we fit into the clockwork of creation—a position that many still embrace, a remnant of the Enlightenment and a position that gives credence to the religious faithful.

This idea becomes most apparent when reading Richard Garfinkle’s novel Celestial Matters. Historically placed about a millennium after Aristotle, Garfinkle’s novel is set in a real manifestation of a Ptolemaic universe: the characters live on earth at the center of the universe, around which circle the ’Ermes, Aphrodite, ’Elios, Ares, Zeus, Saturn, the fixed stars, and the Sphere of the Prime Mover. Garfinkle writes a hard science fiction novel of “alternate science” that could be called a novel of golden age sf, where an almost romantic faith in science can solve the problems of the world and help humanity though their most difficult endeavors.

Yet, science does not represent the only order of this world: there is a connection between science and religion, a mixture of Greek mythology and science that has progressed as if a two-thousand year old view of medicine in this world (one based on humors that is now seen as quaintly naive) was in reality accurate. While religion is an important part of the workings of this world, these are not the gods of Homer, but are more like allegorical representations of the characters’ dispositions and caprices. When Athena speaks through the protagonist Aias, he says something wise so that the other characters feel as if the god is present. Before picking up this book, any reader would be advised to review the Greek pantheon. I found myself having to look up a few names just for some context.

Another part of this combination of science and religion reminds me of the contention in many of the great Greek tragedies between a traditional, superstitious view of the universe ruled by the whims of the gods and one that upholds human reason and intellect as capable of understanding and explaining the world. Sophocles saw these as disparate and irreconcilable views of the universe that cause humans to err, losing faith in their traditions, blinded by the hubris that places humanity in a godlike position. The height of Athenian culture was also a time of insecurity and desperation for many, when the old religious ways were being usurped by a new focus in the powers of the human intellect. The height of Athens would not last for long in our history, but in Celestial Matters, Garfinkle reconciles religious devotion with that of philosophy turned science through an Aristotle that never was.

The heroes of this alternative universe—one that is strikingly similar in many ways—are Aristotle and Alexander, the former for his scientific knowledge and the latter for his military prowess. The culture is right out of Plato’s Republic, where poets are venerated, but banned; where the citizens and scientists are ruled by an elite class of Philosopher-Kings; where this hierarchy is maintained by a race of born Spartan warriors. Aristotle and Alexander represent that two concerns of this culture: military might and scientific positivism.

This western view, that of the “Delian League,” is contrasted with that of the Middle Kingdom, or eastern perspectives of the workings of the universe that prove, when given the chance, equally convincing in their view of how things work.

The lesson of Celestial Matters seems to be a liberal one: that no matter how much we know, there are always other ways of looking at it, other discourses, other orders. We only get into trouble when we privilege one system over another, no matter how certain we are of the Truth. Garfinkle’s protagonists are products of rigid systems, but there seems to be a faith that no matter how ossified the system, we, as humans, can transcend those systems to become more. We are not determined by our nature or our culture, that we are divine in our ability to wonder and imagine new possibilities. Garfinkle’s view depicts two seemingly disparate and irreconcilable cultures coming together for the benefit of something more than their ideas of the world. It’s sf like this that seems necessary in a polarized world like ours. Check it out.

Nice take on Garfinkle’s Celestial Matters—a rich novel, no doubt. I’d like to elaborate a bit on some of your points and make a few of my own.

While having an adventure-story plot, the novel, you’re right, is really about how knowledge systems define “reality” and, consequently, determine our existence. It is about the stories we tell ourselves about the “nature” of reality, the stories that mediate our relationship to the physical world and tell us who we are. The braid of story and science is the realm of technological imagination, and Garfinkle works this terrain as well as any SF writer.

Of course, as you point out, there is more than one dominant knowledge system in the novel—that of the Middle Kingdoms and that of the Delian League; the Kingdoms and the League are the East and the West, respectively. What we discover throughout the novel is that these knowledge systems are at war as much as the Kingdoms and the League themselves, that an ostensibly unspannable gulf exists between the systems. One major difference between the systems is that the science of the Middle Kingdoms is based on medicine, while that of the Delian League stems from warfare. At one point in the novel, Phan, an advanced Middle Kingdom scientist becomes offended when asked by Aias, the protagonist and Delian scientist, if he is a doctor. Phan explains that all scientists are doctors; that’s the area in which they begin their initial training and advance from there. The Akademe of the Delian League, meanwhile, has forsaken the study of history and philosophy and is only concerned with science in the service of military application; the Akademe has lost the ability to reflect on where it has been and the ethics of what it is doing.

The foundation of these knowledge systems, consequently, affect perceptions and interpretations of physical phenomena; in short, each system understands “reality” and develops its science differently. Steeped in philosophy of the Tao, Middle Kingdom scientists manipulate the Xi flow, or energy currents, of objects and people. The science of the Delian League manipulates matter and form. By making both systems valid in the novel, what Garfinkle does is show how interpretations and understandings of physical phenomena construct our realities. And it is precisely through this relationship between the discursive and physical that we construct ideas of ourselves—in the case of the Archons, people of might and reason. At one point in the novel, Aias thanks Klieo, muse of history, for showing him how she can “grip the hearts of men and nations and draw them down paths so disparate that the men of one people cannot speak to the men of the other.” But it is Aias’ focus on history and ethics along with his and Phan’s working together, their sharing knowledge that leads to Aias’ epiphany.

This leads me to the role of the gods in the novel and to what Aias ultimately does with Klieo’s knowledge. I think you’re right when you say that the gods “are more like allegorical representations of characters’ dispositions and caprices.” As I was reading the novel, I thought the same thing: that a character may have an idea or make a decision that comes from his or her own mind but they attribute it to divine inspiration. But I think it’s helpful and important to look at religion, in this case, as another kind of knowledge system, like (and unlike) science. Just as belief in one’s interpretation of the world constructs reality (science), so belief in one’s interpretation of the other-world(s) constitutes a relationship between the two constructing a psychological and emotional system of motivations and consequences (religion). Aias’ faith in the gods is as strong as his faith in science; in fact, it is the gods (in his mind) that lead him to change his mission.

I agree with your conclusion that the lessons of Celestial Matters is that “no matter how much we know, there are always other ways of looking at it, other discourses, other orders.” This is the big message, which we could call liberal or critical, as well as the lesson Aias learns about the ethically moribund Akademe. Also, I think the lessons about religion are positive and liberal as well. Aias’ secular insight actually has a moral basis. The religious message here seems to be, if your religion is telling you to wipe out an entire people, it is flatly wrong. I think what Aias ultimately does with this knowledge is cautionary. With the insight we mention, he does not repudiate all war but a certain kind of war, namely, the kind of war that could escalate to some day destroy all the world. At the end of the book, he says there will still be wars (border skirmishes and the like), but not wars based on ignorance of other knowledge systems by those bent on outright destruction of others.

You’re right to say the novel has Golden Age SF leanings. You mention faith in science to solve the world’s problems, and I would add that it has a similar ethical dimension as well: caution about the very same science hurtling us unchecked toward destruction. In those days, the science of atomic energy was the major concern. Having said that Celestial Matters has Golden Age leanings, I would still put the book in with a new breed of SF that has a critical, almost radical take on history. This is a novel of alternate science much in the tradition of the alternate history novel. But I would place it alongside of Robinson’s The Years of Rice and Salt and Simmons’ Ilium. After all the SF about post- and trans-human futures, it seems that some SF writers are messing around history and myth to explore how these tell us who we are in relation to the world. SF, of course, has always concerned itself with the past to some extent. But I see some of this newer SF radically reconceiving the past and exploring the importance of history to shed light on who we think we are based on the stories we’ve told. We might say in this kind of SF the past is the new future.