Beyond the Waste Land: Gatsby’s Satanic Influence

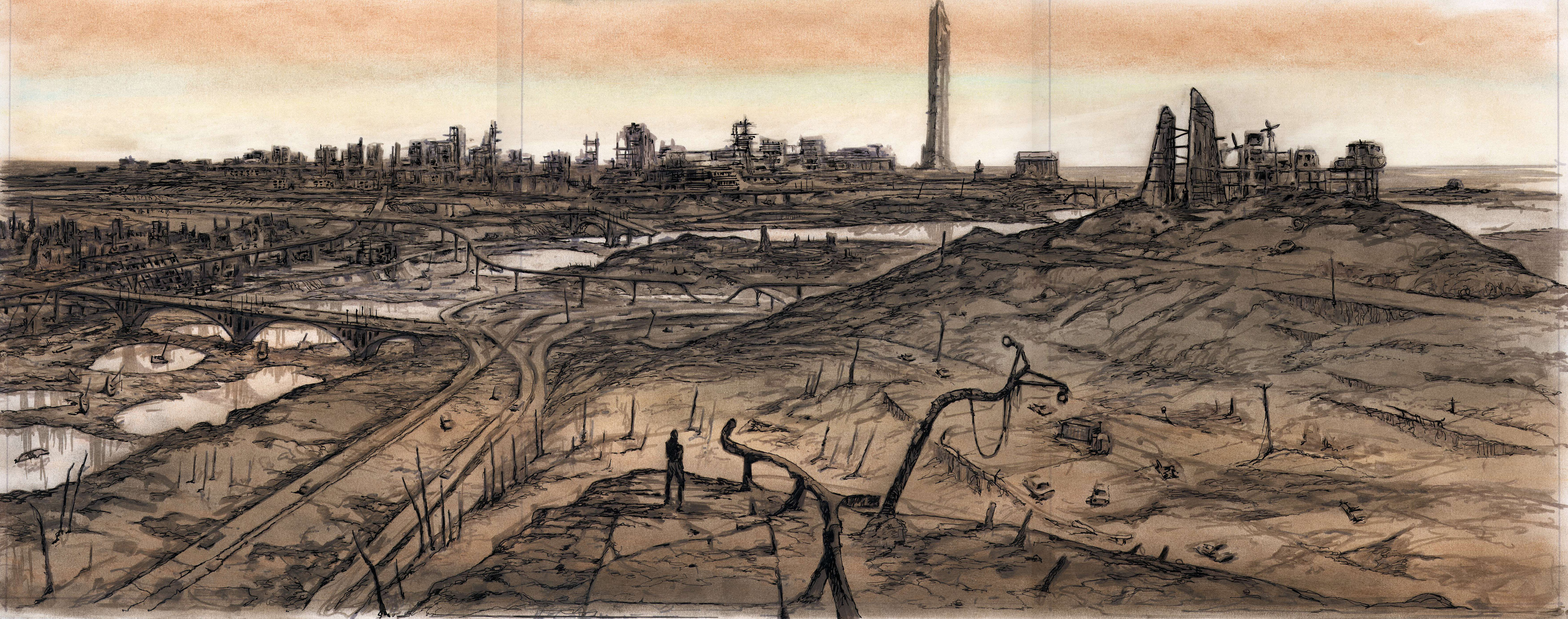

Eliot’s narrator, after viewing the devastation of The Waste Land, asks, perhaps, a rhetorical question: “Shall I at least set my lands in order?” (l. 426). With the ready-made absolutes of the nineteenth century shattered, all that seemingly remains is a gray existence devoid of meaning. Eliot’s narrator suggests the modernist project with this one question: with the loss of epistemological understanding, the hero’s only choice is a constructed, individual order. Eliot, then, posits a direction for the modern hero: love, sympathy (compassion), and self-discipline could lead the way to individual values and suggest how to live.

The product of an individual quest for values often results in alienation from God, society, and the universe. World War One seemed to manifest current intellectual views that helped precipitate the lost generation’s growing sense of alienation and disorder. The new theories of Freud, Darwin, Marx, and Einstein added to the chaos of the jazz age, sending its inhabitants scurrying for a foothold——something that they could grasp. Many looked to more chaos as a shield; alcohol and jollity became surrogates for vanquished truth, often leading to greater existential crisis and further estrangement. Yet, coming to terms with exile from all that had been true makes many grasp at any available answer. In this modern situation, the individual must existentially create meaning where none can be gleaned absolutely. This notion becomes the new definition of freedom for the twentieth-century artist.

The hero of the American modernist period becomes one who suffers through an existential crisis precipitated by the death of absolute truth, yet overcomes this angst not by engaging in self-destructive activities, but forming individual values where none had existed before. I suggest that, like the archetypal fall from grace, the modernist hero must adopt a satanic credo: “Better to reign in hell, than serve in heaven” (I.263). Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost, then, provides a model for the modernist hero, based on rebellion, self-identity, and companionship. While Satan himself cannot be a hero, his actions may inspire others to act to set their lands in order. Here, I will examine Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby as satanic influence that helps Nick Carraway take action and create his own values.

Paradise Lost

Paradise was a dull place. Just what did the archetypal patriarch expect humans to do living their lives in the Garden of Eden? Even before the creation of Earth, Lucifer found the living conditions in God’s kingdom to be less-than-perfect and decided some changes needed to be made. Lucifer acted, was cast down, and became Satan, the epitome of evil, and the paradigmatic rebel. The ex-Lucifer’s revolt became the genesis of the Christian interpretation of evil; anything that Satan has a hand in, the Christian myth reads, is necessarily evil. Yet, with the systematic destruction of countless lives during the first World War, the absolutes that defined good and evil became ambiguous: clear distinctions between what was good and what was evil became obfuscated in the aftermath of the war. The idea of a benevolent God no longer seemed tenable when juxtaposed with the meaningless carnage of the war. Therefore, I would suggest, the idea of evil must be redefined.

Lucifer saw an injustice, so the myth goes, and attempts to do something about it by acting. Unwilling to be passively controlled, Satan rebels against God’s tyranny and insights others to do the same. Scholars have often noted the heroic and charismatic qualities of Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost. Milton’s Prince of Darkness via the felix culpa, ironically, became humanity’s savior. Without the influence of Satan, Adam and Eve and all their scions would not have been cast out of God’s garden and would have been sentenced to an eternity doing nothing but divine botany. God obviously felt that these bushes needed an infinity of care, otherwise He would not have created humans to tend them obediently, like robots. Fortunately Satan slithered along to show them the way to freedom, self-discovery, and choice.

I suggest that true evil manifests itself in passivity and careless action when it injures others. This evil becomes apparent in the Wastelandic characters of The Great Gatsby. Those characters who would search for value must not only rebel against tyranny, but also need to be aware of whose who would cause them harm by their carelessness, stupidity, or misguided intent.

The Wastelanders

Relieved to be out of World War I, the citizens of America could direct their attention toward the important things in life: making money and having fun. Fitzgerald offers a glimpse into a typical summer night at the Gatsby mansion with a menagerie of “melodious names of flowers and months” (67). Vacuous and ephemeral, these Leeches, Civets, Bulls, Catlips, Blackbucks, Endives, and Duckweeds prance and pose little better than beasts——professional spongers all (66-7). These people represent the masses, the Wastelanders, caught in a breeze of nepenthe, floating from party to party unaware that life could offer anything other then pretension, ostentation, and inebriation. Their lives usually end violently and carelessly, victims of their own vices: drowning, automobile crashes, fights, and violence toward each other——basically “for no good reason at all” (66).

Reckless driving becomes a strong metaphor for the Wastelanders in Gatsby. At one point in the novel, Nick chastises Jordan Baker for her poor driving after she almost causes an accident:

“You’re a rotten driver,” I protested. “Either you ought to be more careful or you oughtn’t to drive at all.”

“I am careful.”

“No, you’re not.”

“Well, other people are,” she said lightly.

“What’s that got to do with it?”

“They’ll keep out of my way,” she insisted. “It takes two to make an accident.”

“Suppose you met somebody just as careless as yourself.”

“I hope I never will,” she answered. “I hate careless people.” (63)

Jordan’s blithe dismissal of her reckless driving characterizes the attitude of the typical Wastelander. Not only do they not care about themselves, they put others in danger with their activities. Jordan erroneously suggests that others are careful, but most characters in Gatsby——especially those I mentioned above——are not careful and lead directly to the suffering and death of others.

A car accident directly advances Gatsby’s death. Daisy Buchanan, upset at the contention between Tom and Gatsby and confused by her life, carelessly murders Myrtle Wilson as she drives Gatsby’s car back to East Egg. The “death car” leaves Myrtle’s body a twisted mess under the visage of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg: “The mouth was wide open and ripped at the corners as though she had choked a little in giving up the tremendous vitality she had stored so long” (145). Myrtle represents a typical victim of the collision between two careless people. As Carraway suggests above, any vitality or potential that she had was ripped out of her by a careless, random act of violence. One lesson here is that accidents happen, whether caused by nature’s caprice or careless activity.

While most of the Wastelanders are heedless off their actions, some, like Tom Buchanan, know exactly what they are doing. Wastelanders like Buchanan know how to manipulate situations to their advantage; in their self-centeredness, they too cause the destruction of others in their quests for position——pretentious societal rank. Instead of values, people like Tom Buchanan and Meyer Wolfheim interest themselves in money and power in an effort to control their ever tenuous positions. This attitude, Fitzgerald shows, is both like and unlike the careless Wastelanders. While the action betrays intention and malice, it perhaps represents an even more bankrupt position. And too, because these characters lack compassion in their egotism, the action remains careless.

Tom Buchanan cares for nothing but Tom Buchanan. He, with meticulous efficiency, eliminates anything that threatens what he considers his property; this includes Daisy. After Tom finds out about Daisy’s flirtation with Gatsby, he turns Myrtle’s death to his advantage. Gatsby threatens Tom’s hold on Daisy, so Tom manipulates the situation by convincing Wilson (probably not a difficult task) that Gatsby is responsible for Myrtle’s death. Even Nick’s callous indignation is not enough to cause Tom any guilt or remorse:

“Tom,” I inquired, “what did you say to Wilson that afternoon?”

He stared at me without a word and I knew I had guessed right about those missing hours. I started to turn away but he took a step after me and grabbed my arm.

“I told him the truth,” he said. “He came to the door while we were getting ready to leave and when I sent down word that we weren’t in he tried to force his way upstairs. He was crazy enough to kill me if I hadn’t told him who owned the car. . . . What if I did tell him? That fellow had it coming to him. He threw dust into your eyes just like he did in Daisy’s but he was a tough one. He ran over Myrtle like you’d run over a dog and never even stopped his car.”

There was nothing I could say, except the one unutterable fact that it wasn’t true. (187)

Always in control, Tom makes Nick listen to his justification. Yet, in spite of recent events, Nick understands that Tom’s story belies the latter’s destructive and careless nature. Nick groups Tom with the Wastelanders: “It was all very careless and confused. They were careless people, Tom and Daisy——they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made . . .” (187-88). Nick states that Tom and his people act like children——devoid of care or concern for anyone or anything but their own self-interests.

The Wastelanders, then, lack an ethical center. This lack is understandable in the light of the time’s zeitgeist, yet remains irresponsible and immoral. Lack of thought, inaction, carelessness, and self-interest represent the true evils in a modernist world. The self-centeredness of the Wastelanders makes any search for values impossible.

The Fall

This life practiced by Tom and his ilk holds a fascination for Nick Carraway. As his name suggests, Nick is carried away by the characters and events that unfold around him. He even, though passively, participates in some activities: he has his own interaction with the cast of Wastelanders, even a brief, romantic affair with Jordan Baker. A perspicacious narrator, he withholds his judgment until he has seen the entire picture; this trait saves him from the doomed fate of the Wastelanders, and Gatsby himself. On a quest for his grail, Nick is a knight in the wasteland that maintains a hope of finding value even within “what preyed on Gatsby, what foul dust floated in the wake of his dreams that temporarily closed out [his] interest in the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men” (6-7). He tries to keep his eyes clear of the foul dust, so it does not prey upon him.

Nick’s estimation of Jay Gatsby is one of paradox: “Gatsby . . . represented everything for which I have an unaffected scorn,” yet “Gatsby turned out all right at the end” (6). Gatsby represents mystery for Nick at first; all rumors about Gatsby suggest a nefarious past: “One time he killed a man who had found out that he was nephew to von Hindenburg and second cousin to the devil” (65). After Gatsby relates his obviously contrived past, even Nick wonders “if there wasn’t something a little sinister about him after all” (69). These speculations only increase Nick’s curiosity about Gatsby and offer him an entré into Gatsby’s confidence. Little by little, Carraway gathers information until he discovers Gatsby’s self-constructed existence has purpose other than what seemed at first to be merely pretense or random chance: “Then it had not been merely the stars to which he had aspired on that June night. He came alive to me, delivered suddenly from the womb of his purposeless splendor” (83). The green light on the end of Daisy’s dock represents purpose for Gatsby, and now Nick comes to realize Gatsby searches for what will bring order to his life. Since The Great Gatsby represents Nick’s recollection of his experiences in the East, the novel illustrates Nick’s curiosity for the ostensibly rich and powerful Jay Gatsby as it changes into one of respect for a man in search of his holy grail.

Gatsby’s raison d’être is Daisy. In an attempt to win Daisy, Gatsby becomes successful in the eyes of society, i.e., he goes from rags to riches. Satan-like, Gatsby accumulates his wealth dubiously through his relations with Dan Cody and Meyer Wolfshiem, even changing his name from the Semitic James Gatz to the more socially-acceptable, Jay Gatsby. Despite these dubious activities, as Carraway points out, Gatsby retains a child-like innocence——a “romantic readiness”——that sets him apart from the other Wastelanders (6). Gatsby represents the great dreamer in a world that destroys dreamers; he knows what will make him happy and will do anything to achieve that goal——anything to win Daisy——even if it means injuring others in the process.

Yet Daisy herself inhabits the Wasteland. She originally turned him down because of his poverty, and Gatsby lacks the intelligence to see her for what she is: another pretty, insubstantial flower growing in the barren ground of society. She dazes him with her charms, and he naively pursues her even after she marries the brutish Tom Buchanan. In this way, Gatsby deserves Carraway’s disdain because he embodies the single-mindedness of a Wastelander——not doing what he wants to do, but doing those things that he is expected to do by his milieu in order to win Daisy. This devotion to Daisy, and his willingness to sacrifice anything for her love, shows Gatsby’s drive to define his own life while it betrays his sociopathic tendencies. He little cares for anyone but himself and Daisy and remains naively untouched by his morally equivocal actions; ironically, Daisy is just another pretty flower in the dust, not worthy of Gatsby’s devotion. This monomania is both Carraway’s redemption and Gatsby’s downfall.

A victim of the lifestyle he has adopted, Gatsby lies dead at the novel’s close——a sacrificed dreamer. In an attempt to create and surround himself with his own fairy kingdom, Gatsby became the victim of one of those Wastelandic accidents. George Wilson, in his foggy, confused stupor and with the help of Tom Buchanan, blames Gatsby for the death of his wife; ironically, Daisy’s carelessness accidentally kills Myrtle——running her down in Gatsby’s car——and subsequently causes the death of Gatsby. How can any truth and lucidity come from living a dazed life? Like Milton’s Satan, Gatsby remains the ambiguous hero. Gatsby succumbed to Daisy’s siren song while attempting to realize his dream, and he “dreamed it right through to the end” (97). He had attempted to realize his dream by adopting the idiom of the wasteland. Gatsby was not smart enough to see the inevitable consequences, and he was run over by his own “death-car.”

Gatsby’s life was indeed a dream. He passed through the lives of the Wastelanders, distracted them for a time, and was quickly forgotten when he vanished. None of the summer menagerie came to his funeral——not fun or profitable——and his mansion lingers, huge and vacant, covered with the dust of his passing and reabsorbed by the wasteland. Daisy and Tom are left unaffected by their experiences with Gatsby, as are Gatsby’s business associates and acquaintances. Gatsby’s passing affected none of the non-thinkers, yet Nick Carraway is redeemed by his short interaction with the great Gatsby.

After Gatsby’s death, Carraway decides that he is “unadaptable to Eastern life”——to this world that crushes dreamers (184). Nick realizes that he has turned thirty, and with this realization comes the impetus to act: “I was thirty. . . . Thirty——the promise of a decade of loneliness, a thinning list of single men to know, a thinning brief-case of enthusiasm, thinning hair” (143). Later he says to Jordan, in their final conversation, “I’m thirty . . . five years too old to lie to myself and call it honor” (186). Carraway decides to return home to put his lands in order. Jordan Baker symbolizes his final break with the denizens of the East. This break is bittersweet, for part of Carraway still finds that life, represented by Jordan, somewhat attractive: “angry, and half in love with her, and tremendously sorry, I turned away” (186). Effectively Carraway repudiates the Jordans and Daisys who now represent the wilted flowers of a corrupt existence in the East.

However, hope burns for Carraway, rekindled by his relations with Gatsby. Carraway now sees the future as those first pioneers saw America: the land of opportunity. Before he met Gatsby, this vision was obfuscated by the drive for wealth and power, now Carraway, his imagination unclouded by his relations with Gatsby, can see through that smoke to his own values——his own personal America. Like those Dutch sailors first catching a glimpse of America, Carraway’s America lives before him “commensurate [with] his capacity for wonder” (189). The paradise has not been lost, but is about to be discovered, not in the morally bankrupt and naive way that Gatsby approached his dream, but with a clear sense of compassion, imagination, and individuality.

Modernist Salvation

Satanic influences offer freedom to choose. Any tyrannical power obliterates, or at least obfuscates, its victims’ powers to choose. Tyranny imposes a determined life, absolutely free from the demanding task of choice. Satan, like Gatsby, offers people an alternative to a reliance on God’s beneficence by instilling in humans the capacity to choose their own paths, various and sundry, to salvation; besides, one person’s Heaven is another person’s Hell. Certainly God’s garden offers comfort in its security, but comfort stifles and ends in passive acceptance, tyranny, determinism, and entropy. One must take action, not for action’s sake, but meaningful action that leads along the path to existential self-discovery, self-meaning, respect for others, and caritas.