Student Conferences and Growth

Student conferences are always interesting experiences. I usually have them around midterm, before midterm grades are due and after midterm exams. Often, this is the only opportunity I have to talk with each student, one-on-one during the semester. It’s not because I don’t have office hours, but students rarely, if ever, come to see me — even if they have major problems. I know: I’m intimidating. I hear that one all the time.

I had a student this morning tell me he hates my web site — that it’s too confusing — that it has way too much information. He gets lost. Confused. I asked, as I often do when getting criticism, how I can make it better. He said I should have clear assignments, so students know what to do and when it’s due. He continued, I would have had the proposal turned in on time, if there had been a simple way to type it in or upload it — you know, like D2L.

Maybe these are valid criticisms; maybe not.

He want on to criticize my classroom approach, too. He said I shut a student down when her answer to my question “what are your reactions to today’s reading” was “it was long.” They are so frightened of being “wrong” (his word) in front of their peers, they don’t say anything. This, he suggested, it what lends to the oppressive (my word) atmosphere of my classroom. “I’m normally very out-going,” he explained, “but not in your class. I’ve heard this from many others, too.”

Maybe.

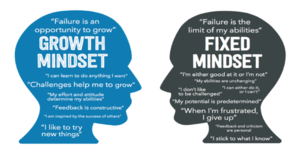

I mentioned the other day that I'm reading Dweck’s Mindset for a learning community. Those with a fixed mindset are out to prove their natural abilities; they see no need for effort, because that shows their lack of ability. I either have it or I don’t, they believe. In her development of this idea, Dweck writes: “John Wooden, the legendary basketball coach, says you aren’t a failure until you start to blame.”[1] This idea resonates with me and describes 45 perfectly.

Now I don’t want to totally discount everything my student was suggesting above, but most of what he said seemed to be an attempt to lay blame on me. When he said that my web site is confusing, I asked how long he had thought that way. “Since the first day.” “Well,” I asked, “why is now the first I’m hearing about it?” More excuses followed, yet, the fact remains that this is the first time I’m hearing about it, when I could have helped to dispel the confusion months ago.

I did not have conferences with my second class, but talked with them about their midterms in class. I told them that I want them all to succeed, so I them them the day to rewrite one of their exam questions in order to increase their grades. Most relished the opportunity. However, as one student left, she said “It doesn’t matter: I’m going to fail anyway.” Classic fixed mindset? While many of the students were keen to put in additional effort, she made it clear to me what she thinks of me and my class by showing her she doesn’t have the natural ability to effortlessly pass my course. I’m sure others felt that way, too.

I am not faultless here. I continue to grow as an educator, and I continue to make mistakes. I know this. I, too, am often guilty of a fixed mindset, but I continue to try. I continue to give it effort. Sometimes, I wonder if I’m the only educator here that challenges students. (I know the answer is no.)

- ↑ Dweck, Carol S. (2016) [2006]. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 37.