Courage through Opposition: The Political Resonance of Norman Mailer[a]

First articulated in his 1957 novel The Deer Park, Mailer’s approach to work and to life echoes throughout his oeuvre: “there was that law of life so cruel and so just which demanded that one must grow or else pay more for remaining the same.”[1] One could even regard this “Mailer’s Law,” as it seems to provide a synecdoche for his career as an artist and public figure. As an exemplar of this early and oft-articulated credo, Mailer never stood still for long. Not one to rest on his laurels or to be dissuaded by critical disapproval, Mailer made strides to, as he states in Advertisements for Myself, “settle for nothing less than making a revolution in the consciousness of our time.”[2] While Mailer could be accused of hubris, his approach to culture and life exhibited a courage to grow in opposition to what he saw as the deadening forces of totalitarianism in America. Mailer viewed political challenge as the moral responsibility of the creative artist — especially the novelist — in maintaining freedom from tyranny. Mailer’s opposition resonates even beyond his death in 2007. This essay examines the political Mailer in the last decade of his life.

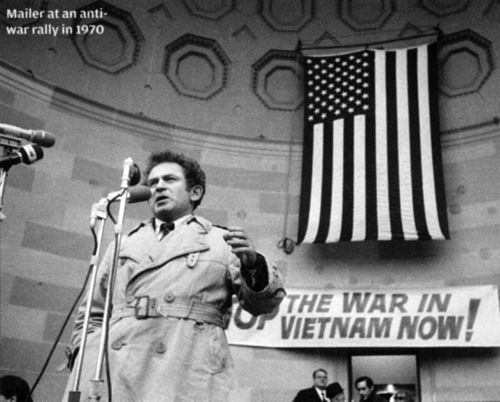

Even more than a decade after Mailer died, his presence may still be felt almost daily. Perhaps it’s because today’s political climate seems to echo the sixties, when Mailer was at his most prominent and influential. His influence during a decade of upheaval, opposition, and revaluation of America, Mailer stood at the forefront. If Mailer wrote about something, that usually meant he was participating in it, thinking about it, and offering Americans alternate perspectives about everything of import. From New York City to Washington D.C., from Alaska to Vietnam, from Zaire to the moon, Mailer was there, prompting Wilfred Sheed to quip in 1971: “As Mailer goes, so goes the nation.”[3] Mailer’s presence, while dominant, was never one expressed with easy or compulsory answers to big questions. More often, he submitted an oppositional view, or as William Prichard recently observed, Mailer met “head-on every sort of public, social, and political phenomenon in order to ‘war’ on them.”[4] Mailer’s estimation of his own political penchants were also elusive if not oppositional. In 1955, Mailer writes “Please do not understand me too quickly,”[5] providing a foundation for his contradictory left-conservatism — a stance that Christopher Hitchens suggests identifies Mailer with “a dark underside” and stands “semi-belligerently as a challenge to those who remain fixed in orthodoxy or correctness.”[6] Mailer saw totalitarianism as the natural state of humanity that “sullies everyone who lives under it,”[7] and therefore opposition to its every form becomes a moral imperative.[8]

Mailer’s penchant for opposition seems germane now in the waning days of the second decade of the new millennium. Journalists trying to make sense of contemporary protest movements, from Occupy Wall Street to Extinction Rebellion, like Francis Wade in “Reading ‘The Armies of the Night’ in an Age of Youth Protest,” look to Mailer’s example for understanding “the curious art of protest, and the dance between authority and dissent.”[9] Others long for Mailer’s voice to offer a way through the current populist movements in politics that seem to have swung the country uncomfortably to the right. In “Mailer on ’Rump,” Paul Baumann compares Mailer’s analysis of Barry Goldwater and his supporters to ’Rump and his with some striking similarities, like how ’Rump taps into current resentments was just the sort of “existential question Mailer had an uncanny ability to illuminate.”[10] Baumann concludes that while Mailer was able to give Goldwater serious consideration, he would have had a field day with America’s current narcissistic president. At the time of his death, many obituaries and tributes lauded Mailer’s influence on American culture and politics and seemed to emphasize the importance of his dissenting voice that refused to allow any tyrannies an easy passage. These are summarized by Bonnie Greer in the Independent: Mailer “believed that telling the truth was the only thing a writer could and should do. Above all, he was never afraid.”[11]

Mailer’s courage as an artist was often aligned with his tough-guy persona, based on his early interest in violence, masculinity, and dissent, and his own unfortunate real-life incidences. Kate Millett argued in 1971 that in Mailer’s violence was inextricably linked with creativity, an inexcusable connection that marked Mailer as an anachronism.[12] Despite Millett’s assessment, Mailer later speaks more soberly about the necessity of courage in fighting for one’s convictions that is not necessarily linked with violence, but still with necessary opposition. In a 1983 portrait by Marie Brenner, Mailer states “As many people die from an excess of timidity as from bravery.”[13] A logical corollary to Mailer’s Law, timidity, repression, and conformity are often linked to cancer in Mailer’s work. In a 1979 interview, Mailer calls cancer “a revolution of the calls” that occurs when an individual lives too responsibly or too much for others.[14] To mitigate the risk of cancer, then, one should live as genuinely as possible — a perennial Mailerian theme. While Mailer’s earlier work was more concerned with the individual and his relation to external forces thattempted to control and direct his life, cancer seems to be a metaphor for a sickness or rot within the body politic in his later thinking. Yet, the treatment remains similar: one must face totalitarianism with courage in order cut out the sickness in the country. Courage, for Mailer, is the virtue to dispel shame — the opposite of love and liberty.[15]

Near the end of Why Are We at War?, Dotson Rader asks Mailer what he most loves about America. Mailer answers that its the freedom he has enjoyed throughout his life that made his work possible, but freedom, like democracy, is delicate, and must be fought for daily.[16] Mailer links freedom in America to its democracy and the responsibility of citizens to undertake the necessary responsibility of maintaining it. Built of the assumption that all humans have value and that people are more good than evil, “Democracy is a state of grace,” Mailer writes, “attained only by those countries that have a host of individuals not only ready to enjoy freedom but to undergo the heavy labor of maintaining it.”[17] In other words, for Mailer, democracy is existential, always presenting new challenges, always changing, and “like each human being . . . always growing into more or less.”[18] Democracy begins with the freedom of its citizens, but a progressive, healthy democracy depends on the ability of its citizens to meet the various forces and challenges that attempt to undermine it.

Mailer saw as his own personal responsibility the necessity to equip Americans with the tools to oppose the forces that seek to undermine their freedom. In his essay “Immodest Proposals,” Mailer maintains that opposition begins with the peoples’ “power to learn to think.”[19] His words are chosen precisely: thinking here is not a static state, but one that must have agency and be able to encounter every new situation in a creative way. Culture, then, becomes a political force that is necessary for creating a populace that can discern critical distinctions and not rely on habit or easy answers to important questions: “Consciousness is enlarged gently and delicately, yet powerfully, and it takes great literature, like great music, painting, and dance, to make that happen.”[20] Since it’s the foundation of liberty, culture is worth “huge, huge risks.”[21] Culture, for Mailer, tends to privilege the written word; therefore, in many ways, democracy springs from its citizens’ ability to use and understand language. In The Big Empty, Mailer opines: “I think a nation’s greatness depends, to a real extent, on how well-spoken its citizens are. . . . As a language deteriorates, becomes less eloquent, less metaphorical, less salient, less poignant, a curious deadening of the human spirit comes seeping in.”[22] The role of the novelist becomes a political imperative: exemplify the language that gives a democracy the tools it needs to thrive.

For Mailer, “truth comes out of opposition,” J. Michael Lennon recently commented in an interview in The Village Voice.[23] His goal, Lennon continued, was not to win arguments, but to get people to think more deeply, more critically, and more creatively about the US and democracy. If, as Mailer states, there are no authorities who have certain knowledge about reality or truth (and that those authorities skew truth because of their powerful interests[24]), then the novel should be an “attack on the nature of reality” in order to approach a “reality varies from chapter to chapter.”[25] Because of its existential nature, reality can never be captured, only reflected. The novelist does this by testing hypotheses that often reflect difficult questions and not quick or easy answers.[26] Through great writing, the consciousness of the populace might be expanded because literature “vibrates within you” eliciting consideration and growth.[20] This duty of the novelist is paramount now more than ever, since the novel is in danger of becoming extinct, replaced by the Big Empty.

Mailer calls corporate capitalism the “Big Empty” — a contemporary manifestation of the center that cannot hold, a century after Yeats.[27] The American corporation is the Big Empty because it stands in direct contrast to that which is genuine and authentic for Mailer: culture, democracy, freedom. The corporation ensorcells the unwary through the language of marketing, distracting concentration, presenting fictions as facts, wrapping us in plastic, and selling us meaning through consumption. It creates new myths — what Mailer calls “frozen hypotheses”[28] — in a post-truth world that, according to Liam Kennedy, seem to be redefining reality faster than writers can explain it.[29]

Kennedy borrows this observation from “Writing American Fiction,” a 1961 essay by Philip Roth. Roth laments a time where reality seems to be outpacing writers’ ability to process it, challenging the usefulness of fiction and silencing many writers: “The actuality is continually outdoing our talents, and the culture tosses up figures almost daily that are the envy of any novelist.”[30] Roth takes many best-sellers to task as being unable to say anything profound about “country’s private life,” but recognizes Mailer as “an actor in the cultural drama” who has become a “champion of a kind of public revenge.”[30] Kennedy suggests that the rise of ’Rump has once again challenged the American sense of reality and longs for another Mailer to lead new armies of the night[29] to insure, in Mailer’s words, we’re “less displaced from reality.”[31]

That which promotes unreality, for Mailer, was aligned with forces that attempted to undermine freedom, dilute democracy, and impose its own myths of dominance and control. Mailer was interested in a geniuneness of individual experience — of an authenticity that was sensitive and creative enough to encounter the unexpected and new in daily life and meet it head-on with courage, rather than retreating into ready-made systems that promote acquiescence and fear. America slipping into fascism was a constant concern for Mailer; it produces ugly people and “sullies everyone who lives under it.”[32] American totalitarianism needn’t be overt. In fact, for Mailer, it often manifested in imposed attitudes of correctness, like patriotism and political correctness. Mailer warns of spreading democracy via the military or capitalism: it must emanate from a people’s internal desire to make the sacrifices necessary to establish and maintain a delicate system.[33] Democracy is not an “antibiotic to be injected into a polluted foreign body. It is not a magical serum.”[24] It depends on a thoughtful populace, not one that’s ready to relinquish its hard-won freedoms during times of crisis and uncertainty. Fascism promises security and certainty, while democracy is “always an experiment” replete with subtleties, ambiguities, and confusion. Fascism provides answers, while democracy depends on questions.[34] For Mailer, we must learn to ask questions and live with uncertainty in order to maintain democracy’s state of grace.[35] Fascism awaits the next national crisis in order to harness fear, uncertainty, and doubt to overrun freedom like a Panzer tank. Mailer was concerned that at time of crisis Americans just might relinquish their freedoms “for a total security that will never come to pass.”[36]

After the terrorist attacks on the twin towers and the Pentagon on September 9, 2001, the Bush Administration ultimately responded by toppling the government of Saddam Hussein through a military invasion of Iraq. In Why Are We at War? Mailer argues that the reason why so many supported this war despite there being, in reality, no justification for it was fear of another terrorist attack on American soil. The Bushites harnessed the almost ubiquitous flag-waving patriotism following the terrorist attacks to carry out its hawkish agenda with little opposition. Because of the “the complete investiture of the flag with mass spectator sports” Mailer writes in 2003, there exists a “prefascistic atmosphere in America already.”[37] Coupled with the use of the word evil — “a narcotic for that part of the American public which feels most distressed” — Bush was able to push America one step further toward fascism. While fear and the desire for security might be the reason why the Bush Administration was able to invade Iraq, it does not explain the underlying reason for the invasion. Mailer’s answer to the question posed by the book’s title proposes that the neo-con, flag-conservatives desired, more than anything, a global empire that sought domestic moral reform.[38][39] Bush’s dream of empire became a moral imperative: an American jihad to set the world straight again. The myth of American exceptionalism demanded that the U.S. focus its military might outward so “moral reform can stride right back into the picture”: “One perk for the White House, therefore, should America become an international military machine huge enough to conquer all adversaries, is that American sexual freedom, all that gay, feminist, lesbian, transvestite hullabaloo, will be seen as too much of a luxury and will be put back into the closet again. Commitment, patriotism, and dedication will become all-pervasive national values again (with all the hypocrisy attendant).”[40] Because “America was becoming heedless, loutish, irreligious, and blatantly immoral,”[41] the Bushites’ only solution was to construct a “morality tale at a child’s level [. . . where] good will overcome a dark enemy”: the “fantasy . . . of bringing democracy to the Middle East.”[24]

As Mailer explains in his essay “America and Its War with the Invisible Kingdom of Satan,” American economic supremacy could also benefit from empire. The neo-cons believed the U.S. economic hegemony could be guaranteed — something that should have and would have happened, they feel, after the fall of the Soviet Union if it had not been for the weak Clinton Administration — by a military empire. The Clinton Administration’s “labile pussyfooting,” Mailer suggests, echoing the right-wing perspective, seems to account for the first major fractures in American politics, resulting in his observation that “Americans are angrier now than at any time I’ve ever seen them.”[42][b] America was prosperous, but the American ethos of “beat everybody” demanded more.[43] Prosperity was not enough when U.S. could have it all. In 1997, Mailer identified the “profoundest contradiction . . . in American life” as the disparity between an identity as a Christian nation and greed.[44] In a few years, the attacks of 9/11 would provide an answer. The Bush-derived myth of American exceptionalism, Mailer observes, allows for the squaring of the hole of American guilt in “the little contradiction of loving Jesus on Sunday, while lusting the rest of the week for megamoney.”[45] The “money-grab” of the nineties, Mailer states, led to a “pervasive American guilt”[46] and a “Christian bad conscience”[47] that needed to be mitigated or even made virtuous. Economic dominance could partake of the myth of empire in doing God’s work.

Mailer concludes in 2003 that the American corporation has become the dominant force in American politics, usurping any true power that democracy might have. We do not get to vote, Mailer argues, “on many an item that truly matters in terms of how our lives are led.”[48] He laments that a democracy cannot really exist in a country where economic disparity is so great. The political influence of what we call the 1% today literally affects the most significant aspects our daily lives: “Was I ever able to vote on how high buildings could or should be? No. Was I ever able to say I don’t want food frozen? No. Was I ever able to say I want tax money to pay for political campaigns, not interest groups?”[48]

Corporate America’s pact with technology — another long-time concern of Mailer’s — just seems to support this dire situation. For example, shortly after Steve Jobs died, Chunka Mui published “Five Dangerous Lessons to Learn From Steve Jobs” that make Mailer seem prescient, if not prophetic. Each of Mui’s lessons underscore the tyrannical atmosphere under which Jobs developed the technology that has become an extension of our hands. Jobs was a micromanager obsessed with secrecy, and he was not afraid to use Machiavellian tactics to achieve his goals. While these traits say much about the current culture in Silicon Valley, it’s Jobs’ famous “reality distortion field” and his declaration that “people don’t know what they want until you show it to them” that seem most germane to Mailer’s concerns. According to executive chairman of Google Eric Schmidt, Jobs was “so charismatic he could convince me of things I didn’t actually believe.”[49] This issue deserves to be nuanced further than space allows here; however, in a Mailerian vein: how could a corporate culture like Jobs’ produce anything healthy for democracy? What do we willingly relinquish of ourselves when we pick up an iPhone or sit down in front of a screen? Some form of this question is as old as technology itself, but maybe we find ourselves at a unique point in history where technology is so evocative and addicting that it’s threat is now most profound. Mailer tells Rolling Stone in 1999 that technology threatens to sever “our connection to existence itself.”

Mailer seems also to have foreseen at least some of the consequences of the Internet of Things. He long disparaged plastic as a metaphor for the Big Empty and technology’s deadening effect on our lives: “The aim of technological society, ultimately, is to work everything over to plastic.”[50] The “pall of plastic” cheapens our lives and the environment, isolating us from everything essential and genuine.[50][47] Technology sells what Mailer calls a “Virtual Reality,” or “closed system, a facsimile of life,” that exists in the language of marketing.[51] This VR, he argues, substitutes power for pleasure making us narcissistic demagogues. Like a demon whispering in our ears, it promises us power, but only ends up robbing us of something essential: cutting off our senses and taking a “psychic toll.”[52] Marketing, Mailer stated, creates a culture of interruption that leads to a deterioration of concentration — an idea that sounds particularly prescient in a world of ubiquitous mobile technologies.[53][c] Like plastic’s affect on the body, looking at a screen all day exerts a “spiritual punishment”[54] that dilutes and deadens our powers of concentration and allows VR (unreality, myth) to take more control of our lives.[51] When knowledge is just a Google search away, its purchase is cheapened.[55] Mailer seems to suggest that like anything worth having, knowledge should entail some struggle, some courage.

Politically, the last years of Mailer’s life were defined by the terror attacks of 9/11. Much of his writing during that time is defined by the new political consequences they precipitated. In his 2004 essay “Immodest Proposals” he writes “Terrorism, in parallel with cancer, is in total rebellion against the established human endeavor.”[56] Terrorism, in a final estimation, was the contemporary manifestation for Mailer in rallying those forces of tyranny that stifled growth, that keep us the same, that keep us diseased. The rot within American democracy, started by greed, technology, intolerance, moral righteousness, was only fueled by 9/11, like a carcinogen that feeds a malignancy. The subsequent spread of unreality only promoted more flag-waving, fears, unjustifiable wars, and ultimately an economic crisis that Mailer did not live to see and that might have propelled one Barack Obama to the White House on a platform of hope. Obama was not a panacea for these ills. In fact, his administration might very well have further fueled the flame of rage that Mailer observed at the end of the twentieth century leading to the populace movement gave ’Rump the presidency.

Like many journalists, we can only speculate what Mailer would think of our interesting times. We could, like those mentioned above and others, long for another Mailerian voice to help guide us through these dark times. Yet, if we give our finest attention to Mailer’s legacy, it still resonates and offers tools for thought and action. Mailer’s outrage — “The shits are killing us.” — continues to echo and could still serve as a cry of defiance as our democracy — and those around the world — remain under threat. The remaining words belong to Mailer: “This country was founded, after all, on the amazing notion (for the time) that there was more good than evil in the mass of human beings, and so those human beings, once given not only the liberty to vote but the power to learn to think, might demonstrate that more good than evil could emerge from such freedom. It was an incredible gamble.”[57]

Notes

- ↑ First Draft completed on 11/15.

- ↑ See Coppins (2018) who posits that Newt Gingrich, Speaker of the House during much of the Clinton Administration, laid the groundwork for the rise of ’Rump in his attack on civil politics: “he pioneered a style of partisan combat—replete with name-calling, conspiracy theories, and strategic obstructionism—that poisoned America’s political culture and plunged Washington into permanent dysfunction.”

- ↑ The iPhone was introduced in June 2007, less than 5 months before Mailer’s death.

Citations

- ↑ Mailer 1957, p. 294.

- ↑ Mailer 1992, p. 17.

- ↑ Sheed 1971, p. 17.

- ↑ Pritchard 2016.

- ↑ Mailer 1992, p. 262.

- ↑ Hitchens 1997, p. 116.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, pp. 94–5.

- ↑ Mailer 2003, p. 53.

- ↑ Wade 2019.

- ↑ Baumann 2016.

- ↑ Greer 2007.

- ↑ Millett 1970, p. 321.

- ↑ Brenner 1983, p. 32.

- ↑ NcNeil 1979, p. 49.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, pp. 143–45.

- ↑ Mailer 2003, pp. 110–11.

- ↑ Mailer 2003, p. 71.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 78.

- ↑ Mailer 2004, p. 569.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Busa 1999, p. 31.

- ↑ Hitchens 1997, p. 126.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 123.

- ↑ Brady 2018.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Mailer 2005.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, pp. 68, 70.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, pp. 66, 98.

- ↑ Mailer 2006, pp. xv, 54.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 74.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Kennedy 2017.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Roth 1961.

- ↑ Mailer 2004, p. 566.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Mailer 2004, p. 565.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 11.

- ↑ Mailer 2007, pp. 75, 77.

- ↑ Mailer 2003, p. 567.

- ↑ Mailer 2003a, p. 542.

- ↑ Mailer 2003, pp. 51–3, 57.

- ↑ Mailer 2003a, pp. 540.

- ↑ Mailer 2003, p. 52.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 101.

- ↑ Hitchens 1997, p. 121.

- ↑ Mailer 2003, p. 46.

- ↑ Hitchens 1997, p. 120.

- ↑ Mailer 2004a, p. 572.

- ↑ Mailer 2003, p. 108.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Binelli 2007, p. 69.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Mailer 2003, p. 104.

- ↑ Mui 2011.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Mailer 2003, p. 92.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Mailer 2004, p. 554.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 6.

- ↑ Mailer 2003, pp. 89–91.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 5.

- ↑ Mailer & Mailer 2006, p. 8.

- ↑ Mailer 2004, p. 567.

- ↑ Mailer 2005, p. 569.

Works Cited

- Baumann, Paul (March 23, 2016). "Mailer on 'Rump". Commonweal. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- Binelli, Mark (May 2007). "Norman Mailer". Rolling Stone. pp. 69, 72.

- Brenner, Marie (March 28, 1983). "Mailer Goes Egyptian". New York Magazine. pp. 28–38.

- Busa, Christopher (1999). "Interview with Norman Mailer". Provincetown Arts. pp. 24–32. Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- Coppins, McKay (November 2018). "The Man Who Broke Politics". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- Greer, Bonnie (November 12, 2007). "Farewell to a Feisty, Fearless Keeper of the Flame". Independent. Retrieved 2019-11-09.

- Hitchens, Christopher (1997). "Norman Mailer: A Minority of One". New Left Review. 22 (March/April): 115–128.

- Kennedy, Liam (January 20, 2017). "The 'Rump era has begun – how can we make sense of it?". The Conversation. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- Mailer, Norman (1992) [1959]. Advertisements for Myself. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP.

- — (January 23, 2005). "America and Its War with the Invisible Kingdom of Satan". Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- — (1957). The Deer Park. New York: New American Library. p. 294.

- — (2004a). "The Election and America's Future". In Sipiora, Phillip. Mind of an Outlaw. New York: Random House. pp. 571–74.

- — (2003a). "Gaining an Empire, Losing a Democracy?". In Sipiora, Phillip. Mind of an Outlaw. New York: Random House. pp. 540–542.

- — (2004). "Immodest Proposals". In Sipiora, Phillip. Mind of an Outlaw. New York: Random House. pp. 550–570.

- — (2003). Why Are We at War?. New York: Random House.

- —; Lennon, J. Michael (2007). On God: An Uncommon Conversation. New York: Random House.

- —; Mailer, John Buffalo (2006). The Big Empty. New York: Nation Books.

- Masciotra, David (April 2, 2017). "Donald 'Rump: A Bigger 'Factoid' President than Nixon?". Salon. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- McNeil, Legs (September 1979). "Norman Mailer: The Champ of American Letters Takes All the Tough Questions on Art, Life, Death, Love, Hate, War, Drugs, Etc., from Punk Contender Legs McNeil". High Times. pp. 43–47, 49, 51–53, 55, 107–109, 111, 113, 115, 117. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- Millett, Kate (2016) [1970]. "Norman Mailer". Sexual Politics. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 314–35.

- Mui, Chunka (October 17, 2011). "Five Dangerous Lessons to Learn From Steve Jobs". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- "The Party". Rolling Stone. December 30, 1999. p. 110.

- Pritchard, William (November 24, 2016). "Stormin' Norman". Washington Examiner. Retrieved 2019-10-01.

- Roth, Philip (March 1961). "Writing American Fiction". Commentary. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- Sheed, Wilfred (1971). "Norman Mailer: Genius or Nothing". The Morning After: Selected Essays and Reviews. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 9–17.

- Wade, Francis (August 12, 2019). "Reading 'The Armies of the Night' in an Age of Youth Protest". LA Review of Books. Retrieved 2019-09-15.